The will to perform and make progress has a long and enduring history in white America. When colonizing Europeans first arrived on the American continent, pilgrim communities advocated dutiful and strenuous work, hard labor, and, above all, “good works.” This was a motivating ethic: the more diligent and hardworking people were, the more likely they were to align their moral compass to God’s will and achieve salvation. They thought they could influence their own personal destiny, their karma, via hard work: since God worked through them, the Puritans were exercising God’s will.

This belief is still rampant today, as people strive to build their stock market portfolios, buy bigger houses, and gain a step up the social ladder. However the quest to realize the state of yoga necessitates something altogether different. While some effort is certainly required, one cannot simply apply a Calvinist value system to a yoga practice and expect to achieve enlightenment.

See also Pranayama 101: This Moving Breath Practice Will Teach You to Let Go

Who is "the Striver?"

For those of us raised under the influence of the Protestant work ethic or in a Judeo-Christian background, there is an implicit motivating drive to succeed. This drive has tremendous sway over much of the population, motivating people’s thoughts, beliefs, dreams, and goals. In a culture of strivers, success or failure, gain or loss, good or bad are always on the line. The pervasive influence of this force goes largely unacknowledged until, in quiet moments of reflection and contemplation, you shine the lantern of your awareness on your own inner striver.

In the second half of my practice life, I have spent precious time reflecting on the origins of my own inner striver. My father was an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church, as was my grandfather and his father before him. Even though I was not actively raised in a church community, the Protestant ethic circulated through my bloodstream. When I first began yoga, invisible forces urged me on, motivating me into handstands and backbends. I was under the spell of familial and cultural assumptions as I strived toward gain and sought approval. These were forces that had been set in motion long ago, persuasive forces much bigger and more impactful than my short lifetime.

It has taken me many years to be able to identify the underlying forces at work in me. This reckoning has required patience, perseverance, and real faith. Countless times I have posed these questions to myself: What am I yoking to? Who is the striver? And what is there to gain? It has been like an archeological dig, sifting through layers and layers of personal history. In the way that an archeologist excavates an ancient site using small picks, trowels and brushes, quarrying the depth psyche requires painstaking and delicate work. Through contemplation and insight meditation, I have sifted through many layers of karma—hope, fear, and longing that left their imprints on the soft sand of my soul.

See also Is It Adrenal Fatigue? What You Need to Know if You Feel Tired All the Time

Integrating “The Striver” into our Signature Self

I think each of us is replete with artifacts from our familial and cultural ancestry, encoded like DNA into our skin, bones, and flesh. When we first adopt Eastern practices, such as yoga or qigong, we attempt to break free from the archival material of our personal history. While the first half of a practice may involve assuming the garb, speaking the lingo, and performing the exotic rituals of a foreign land, in the second half of the journey we must circle back home to integrate the personal history of our own signature self.

The challenge of working with the striver is not merely a twenty-first-century dilemma. On the map of the Eightfold Path, right effort speaks to the importance of not pushing too hard, on the one hand, and not conceding to sloth and torpor, on the other. The Buddha knew all too well the pitfalls of excessive effort. At the outset of his spiritual quest, he put himself through trials of extreme severity and self-punishment. He attempted to overcome his body and mind by force of will through tapas (asceticism). Through fasting, pranayama, and yoga, he pushed himself to the brink of self-immolation. Having suffered and endured corrosive self-mortifying practices, he later espoused the Middle Way, which favors neither indulgence in sense pleasures nor strenuous, backbreaking practice.

See also Pranayama 101: This Moving Breath Practice Will Teach You to Let Go

In the course of a day, whether on or off the mat, right effort requires moment-by-moment negotiation. We must ask ourselves, Am I overexerting? Or am I too passive? Right effort (or what I like to think of as balanced effort) is not a practice that we realize once and for all and then move on. We must embody balanced effort in the way we exercise, study, raise our children, communicate with our employer, and wash the dishes. In yoga, we must seek the middle ground of right effort within every pose, every pranayama breath, and in every attempt to quiet the flurry of thought in meditation.

Realizing right effort in the arc of daily life is critical to wellbeing. Off the mat, when we push too hard, we are prone to stress, anxiety, and exhaustion. On the other hand, when we fall short and fail to apply ourselves, we may never realize our potential.

Skillful action suggests the delicate balance between alertness and ease, resiliency and yielding. Right effort must be fueled by enthusiasm, focus, endurance, and grace.

Through right effort, we come to a part of the journey that the ego-self could never imagine. We enter territory where there is nothing to get or grasp, and there is no more becoming. With the mind empty and attentive, we come into a presence that evades definition and cannot be put into words. It is a strange state of grace, one that always escapes definition. It is like being filled by vast, wondrous, open space.

See also How to Cultivate More Energy Through Your Inhalations

Pranayama Exercise to Find Middle Ground

Begin this pranayama practice by lying on a bolster or folded blankets elevated four to six inches off the floor, so that your entire spine is supported. Place a small blanket or towel under the back of your head so that your cranium is propped upward and slightly higher than your neck. Be sure that your spine is centered on the bolster and that your lungs spread laterally away from the midline.

Once you lie down, allow your body to be completely still and observe the fluid movement of your breath. At the start, breathe naturally, letting your breath flow of its own accord. Sense and feel the texture and consistency of your breath as it brushes against the back of your throat. Remain for several minutes simply observing the inherent motion of your breath.

See also Pranayama 101: This Mindful Breathing Practice Builds Ease After Asana

Then bring your awareness to your inhalation. Observe the beginning, the middle, and the top of your in-breath. Carefully, and with real finesse, actively expand your inhalation. In the same way that a balloon fills with air, sense the expansion of your lungs against your back ribs, side ribs, and front ribs. Practice right effort as you breathe in. Avoid being greedy and forceful by attempting to take in the maximum amount of air. This violates the spirit of pranayama. Rather, yield to the breath in the way that tall grass yields to the wind, moving in time with the current of the air. Right effort requires exquisite listening. If you overexert in pranayama, it will cause strain in your intercostal muscles, your diaphragm, and the visceral membranes around your lungs and heart. Use just the right amount of force to expand. Pranayama should never be conducted through willful effort.

Now breathe in halfway, pause, and retain your breath for several seconds. Breathe in again toward the top of your lungs. In the pause, allow your awareness to soak inward. The more you are able to soak inward, the more you will relinquish control over your breath.

Next divide your inhalation into two parts, pausing first at 30 percent capacity, then again at about 60 percent capacity, before breathing to the top of your lungs. Have an intention to receive your breath rather than striving to fill your lungs to capacity. Find right effort in pranayama, the delicate middle ground between too much effort and too little. Practice this technique for ten minutes before letting your breath return to normal. Lie in Savasana for several minutes before coming up to sitting.

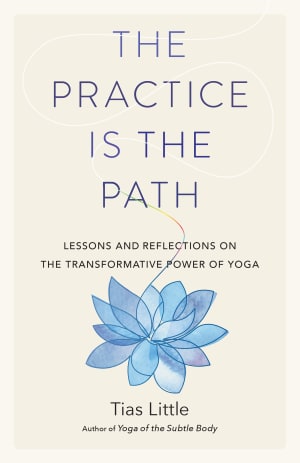

Excerpted from The Practice is the Path by Tias Little, Shambhala Publications, Inc., 2020. Reprinted with permission. Edited for context and brevity.

Want to study with Tias? Join him this Thursday at 11:30 am EDT for a live webinar, Free Flow for Energy & Deep Rest. Through a discussion and practice, you’ll learn how to open your nadis, fascia, and joints in order to facilitate the flow life force and enhance circulation. Learn more and sign up here.